Illegible Genius: Women & Asemic Writing | Jamie Johnston

December 1, 2020

Skira, 2020

What is possible when writing is liberated from the need to communicate? When the signifier is severed from the signified, what new apertures of meaning open for a mark on the page? This was the central question proposed by Scrivere Disegnando, an exhibition last summer in Geneva, Switzerland. The accompanying catalog, Writing by Drawing: When Language Seeks Its Other (Skira, 2020), is not only a brilliantly arranged documentation of the works presented there, but an exceptional expansion on asemic writing: that is, writing which conveys no semantic value.

Unintelligible expression is an obvious paradox. Yet within such a paradox a space for the indeterminate emerges. Writing by Drawing explores this space in the work of 93 trained and self-taught artists starting from the early 20th century. In his opening essay, the exhibition’s co-curator Andrea Bellini embraces the diffuse subject of “imaginary language,” acknowledging the history of linguistic experimentation in movements such as Dada, Fluxus, and Futurism. Yet Bellini turns away from these associations to focus on the “shadow side” of writing, where signification pools and is unspeakable. Here, we observe the reclamation of the mark and the physical act of making it.

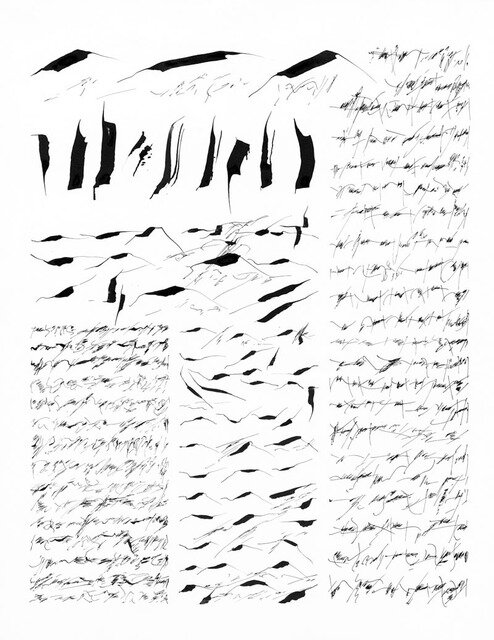

Mirtha Dermisache, Newsletter, 1999, India ink on paper

When the Argentinian artist Mirtha Dermisache wrote her first book, Libro No. 1, in 1967, it consisted of 500 pages of illegible writing. She employed a style of prosodic image-making in the framework of literature, but resisted all its communicative conventions. The work indulged the act of writing itself, creating a new destabilized dimension of meaning. Her subsequent work, featured in the catalog, extended to newspapers, notebooks, and letters with words replaced by thick, horizontal shapes, delicate slanting lines and irregular inky marks arranged specifically on the page, maintaining echoes of their respective forms. In 1971, Roland Barthes wrote Dermisache a letter praising her writing for being “neither figurative nor abstract,” but rather an expression of “the idea, the essence, of writing.” Barthes, ever an antagonist of the bourgeois language structure, revelled in Dermisache’s illegibility as writing’s return to its own truth. The work is unspeakable, but abundant in content.

In the work of Irma Blank meaning bends backward, into the act of handwriting. Blank’s work began after she moved from her native Germany to Sicily in 1955. Unable to speak Italian—this encounter of the most familiar confrontation of language’s limitations—revealed to her that “there is no such thing as the right word,” not even in her mother tongue. Her Eigenschriften series, translated as “self-writings” or “writings for oneself,” became an exercise in self-expression and escape. Tightly woven nets of illegible script create an image of ordered repetition that both declare and dissimulate. The marks are the same but always different. Describing her writing as a “demonstration of movement,” Blank conveys the human experience in it: “it’s simply because of what they say. I am; here I am,” spoken in a language that does not belong to any culture, but might belong to them all.

This compulsion toward a universality of language inspires many artists in the book. Philosophers such as Heidegger, Wittgenstein, and Walter Benjamin grappled with the idea of a unifying, essential language. The meticulous intensity of Henri Michaux’s mescaline drawing illustrates his pursuit of the same. Having deemed the system of written language too slow for human thought, Michaux experimented with a new type of “elsewhere,” hoping to find a language somewhere in between writing and drawing that might capture the immediacy of consciousness. The specific and exhilarating tensions in his drawing remind us of Walter Benjamin’s assertion that language does not facilitate communication but the revelation of being.

What and whose being, however, can be an unpredictable and elusive authority. The exhibition itself opens with the work of Swiss spiritualist and heralded muse of the surrealists, Hélène Smith, who with the help of her spirit guide Léopold traveled to Mars and communed with disembodied extra-terrestrials. Smith’s journeys were recorded in fragmented messages written in a Martian alphabet that was later translated by the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure. De Saussure identified these writings as a distinct language derived from French idiom.

Mystics, mediums, and mental patients frequently occupy the shadow side of writing and exemplify asemic writing’s return to the body. The impulse to record regardless of articulation can express a kind of haunting performed by the living hand, as in the work of Emma Hauck. Although she longed to live a traditional life as a mother and wife, Hauck suffered a deep pathological aversion to her family. Believing that she had been contaminated by her two daughters and poisoned by her husband’s kiss, she was institutionalized in 1909 and declared incurable. Until her death in 1920, Hauck wrote hundreds of impassioned, pleading letters to her husband, which often consisted of a single phrase, “Come Sweetheart,” or simply the word, “Come.” Filling the entire right side of a page, the words overlap and merge, creating layers so tightly compacted they form a depth of abstraction. These vibrating tangles of despair are mirrored by a neat and legible address printed carefully on the left side of the page, indicating the deliberateness of the scrawl. A hand making marks becomes a statement of presence like a never-ending echo.

Jamie Johnston is a writer from Superior, Montana, who lives in Brooklyn, New York.