As With All Warriors of Love: A Conversation with Rihab Essayh | Georgia Phillips-Amos

December 13, 2022

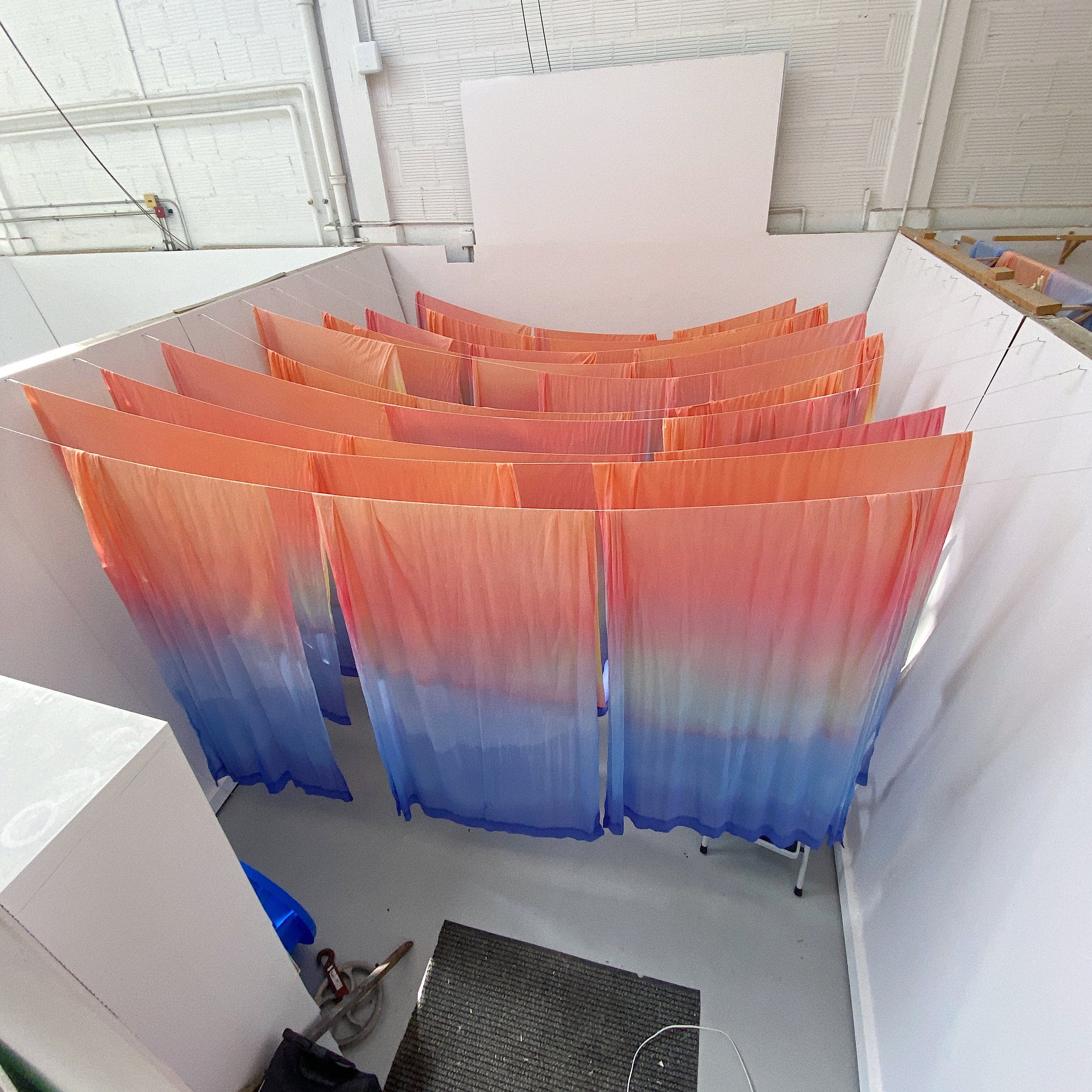

Rihab Essayh, As With All Warriors of Love, 2022, installation, McBride Contemporain | image: Guy L’Heureux

Rihab Essayh (b. 1992) is a Moroccan-Canadian visual artist with a practice of world building. In her hands, natural fibres – muslin, cotton velvet, silk organza, and habotai – envelop gallery spaces whole. White cubes become landscapes that evoke Ernesto Neto’s somatic crochet works and Senga Nengudi's visceral nylon webs. Essayh’s mode of installation invites viewers to come and stay in the presence of large-scale drawings of dancers, projected video performance, and textile poetry set within breathing walls of hand-dyed fabric.

Essayh’s four solo shows in 2022 include I dream of a soft oasis at the Art Gallery of Guelph, of longing and song birds at Union Gallery in Kingston, dwelling for the dear one at Arsenal Toronto, and, most recently, As With All Warriors of Love at McBride Contemporain in Montréal. Images from the latter accompany our conversation. From the sunset-on-sand coloured sofa cushions and their built-in sound system to the hand-stitched poetry evocative of the video performer’s ethereal costume, every element in the gallery space is Essayh’s singular vision and manual labor. Visitors are not just welcome guests but a critical part of the work’s activation. A portal opens onto a stage that promises there is another, less ironic, less defensive, more nurturing and radically soft way to make and experience visual art.

—Georgia Phillips-Amos

Georgia Phillips-Amos

Your current major works are gossamer worlds. They are as soft and complex as cobwebs. Is there a place, a landscape in your life, that is being evoked?

Rihab Essayh

I like this word gossamer. I keep saying I am making installations, but it is more like world-making. Being in Guelph during the pandemic has been very alienating, and I have just been meandering and daydreaming and wandering in memories of joy. Times with my friends in Montréal or memories of being a kid in Morocco. These are not all a single location but a similar feeling.

I have been taking inspiration in the North African peninsula, and taking pride in my Moroccan heritage and in my SWANA (South West Asian and North African) identity. I’ve been thinking of spaces that evoke a sense of warmth and vastness. Not vastness as in the sublime but vastness as in “this could be welcoming.” I have been missing my friends and wanting to make a space where we could be together.

Rihab Essayh, As With All Warriors of Love, 2022, installation, McBride Contemporain | image: Guy L’Heureux

The references for my recent work are North Africa and the sunset here in Guelph, but this also belongs to its own reality: my own world of softness. I was thinking of people first and this idea of having somewhere that feels vast but warm. Not hot, but warm. You know that movie Confessions of a Shopaholic? It is so bad, but it has this quote about a feeling: “warm butter sliding down hot toast.” You see someone and you feel yourself melting in joy and warmth. How can that feeling be evoked?

GPA

Are digital worlds or game worlds also an influence?

RE

I was more interested in the digital before the pandemic. I was interested in hypothetical spaces, in sci-fi and AI. It is often a woman in sci-fi movies who is somehow limited by her digital parameters, either in space and time or in her programming. But for this world specifically I didn’t want to deal with the digital. I was longing for tactility during the pandemic and working with fibres meant I could constantly be touching something.

Rihab Essayh, As With All Warriors of Love, 2022, installation, McBride Contemporain | image: Guy L’Heureux

We are supposedly more open digitally because there is a marketability for this, but it is a filtered vulnerability, an aesthetic one. Online you can be vulnerable because it becomes content that can be consumed. Now, I don’t need to know that world – we’re all living it firsthand, and, I mean, it is depressing. We’re longing to be with people even though we can connect online. It has shown the flaw in online socialization. A lot of our language is body language. It’s in warmth. It’s the silence of being together.

GPA

I’ve felt that teaching online and not sharing a sense of presence with the students.

RE

When people say to me “you have a good online presence,” I’m like, “No, you are talking about my marketability.” The pandemic has shown me that even with its practicality, online life is not a substitute. It’s a compromise, not a substitute.

GPA

Are there specific science fiction worlds or characters that appeal to you?

RE

I generally love Alex Garland’s films, such as Ex-Machina and Annihilation. I tend to gravitate toward the psyche of the main character. Regardless of the magical space, the psyche is what interests me and these situations where the psyche is pushed to an extreme.

In Annihilation, they are all coming in with their own trauma and constantly mutating. You come into this beautiful shimmer. It’s about a space of healing and acceptance and about how, when you are dealing with trauma, everyone copes differently with the change. How can you translate that emotional process, that change, visually? There is something freeing within sci-fi versus a drama where you get all this context. In sci-fi you don’t have to do that.

GPA

You have the speculative element. In Never Let Me Go, they are being harvested for organs and think they can survive if they prove they’re in love.

RE

There is always something about love with AIs trying to prove their humanity. I want that. I want love to be the element that makes us better. I don’t want to say love is the essence of our humanity, but it is a massive factor. I am a romantic. I’m not in a relationship but I have so much love for my support system, for my family, and even for strangers I don’t know. I’m not an optimist. I am extremely pessimistic. But I have love.

Rihab Essayh, As With All Warriors of Love, 2022, installation, McBride Contemporain | image: Guy L’Heureux

In my thesis defense, the only question that made me cry was my prof asking, “What is your definition of love?” Because I finished a poem with, “The only way to conquer the harshness of this world is with the strength of our love, so therefore I love you completely.” I said, “That is not a two minute answer!” This got me thinking about love as this effervescent sense of hope, not because you want something better but because you have to believe people are better. It’s not a material exchange.

GPA

It’s a state.

RE

Yes, it is a state of being. I cried trying to answer that question.

GPA

I’ve been wondering if you plan an installation like an architect, mapping out the elements – the walls, the furnishings – or do the elements come one by one?

RE

I tend to have lucid visions of my work, where I know exactly what I want. For a long time I’ve wanted to make a body of work where people lie down. I don’t see horizontality in the position of the viewer often. Usually everything is at eye level. In this case, I started experimenting with pillows on the floor and a wooden platform with sound coming from below. This developed into: “I don’t want a white cube, I want a soft cube. How can I make this? How can I be better at world building?”

Rihab Essayh, process image, 2022

I do a lot of sketches and plans. A lot of my ideas end up being too expensive to test. I plan and plan and do it in one shot, hoping for the best. I feel so strongly in my conviction that there is a process of relief in making even if it doesn’t work out. It is through the process of making that I realize different things I need. In this case, I knew I wanted curtains, carpets, pillows, and I wanted to have a live performance, actually, but that shifted toward the video. That was my only compromise.

GPA

Was that for practical reasons?

RE

That was completely for financial reasons.

GPA

So you started with positioning the viewer and sound?

RE

Yes. There was something about that idea of positioning the viewer horizontally which was enticing for me. This was after going to the Venice Biennale and seeing the operatic video work of Chloe Lüm and Yannick Desrenleau. Since 2019, I had been working on an idea for an exhibition that evokes a domestic space the size of my bedroom, but my idea shifted from the domestic to the oasis. The process comes from a conviction that this thing needs to exist.

GPA

What needs to exist is a whole world?

Rihab Essayh, process image, 2022

RE

This needs to exist! So I will try to make it. As I make the work, if people start telling me no, I don’t feel defeated. Instead I say, “Ok, let’s problem solve this.” And there is so much joy in that process, regardless of whether the piece I imagine gets finished.

GPA

Have people surprised you with how they interact with your work?

RE

I love how people travel in the space. I love how people lay down on the sofa and the floor pillow. We were supposed to have a live performance, and yet this in itself becomes quite performative in the gallery. There was a kids’ camp in the summertime at the Art Gallery of Guelph, and the ways the kids interacted with the work surprised me. My work became their relaxation room. I knew I wanted it to be soothing and warm, but this took me off guard. From now on I want all my work to be judged by kids first. They have a sense of wonder and observation that is so much more raw. We are always judging and contextualizing what we see and they are just in it.

GPA

They’re also ready to be transported.

RE

They accept that it’s imaginary. They accept the wonder of it. I saw kids sleeping on the floor, sitting on the top of the sofa, sitting on the floor against it.

GPA

Did you feel protective over the objects?

RE

Right now, I’m showing work in Kingston and a couple of things broke. I think, maybe I made a material mistake and that’s their lifespan. When I am inviting the viewer to interact with the work I can’t be precious about it. With All the lost things I miss (2019) I put gloves on the floor for people to interact with the work, but quickly all the mylar that I’d engraved with poetry was twisted and covered in fingerprints. In the end, I think that is kind of nice. The work is lived in and has been properly experienced.

You can’t be too precious with interactive work. Otherwise, you are not inviting the viewer in. It has to be strong enough to sustain the viewer’s exchange with it, not so precious that the viewer feels guilty for interacting with it. I think the museum context already hinders that sense of interaction. In this case, the whole white-walled institutional space got covered.

Rihab Essayh, As With All Warriors of Love, 2022, installation, McBride Contemporain | image: Guy L’Heureux

GPA

This embodies the radical softness referred to in the artist statement. When did you first connect with this concept?

RE

The first person I encountered it through was Alberta Whittle. I now know the term comes from Laura Mathis, but my intro was through Whittle. I remember hearing her say that especially when you are making installation work that makes demands of the viewer, you have to show them care. You are asking the viewer to spend time and interact, so you have to make the space suitable for them. Not just suitable to the work but to the viewer too.

GPA

Is radical softness a fixed idea in your mind or does it change?

RE

I think it is constantly changing. Lora Mathis’s definition says talking about emotion is a political move. Radical softness in feminist movements is about shifting our perspective on emotionality as weak. Why is it feminine to be emotional? Why is that a sign of weakness?

What I see as the demands of radical softness in my work are in terms of equitable care and attention for everyone to be heard with empathy and respect. This means a shift in position from one of defensiveness and impenetrability to openness and vulnerability. It is about shattering the shame around emotionality, dismantling this toxic patriarchal system that codes emotions as weak. To me radical softness is reconsidering what strength looks like. It looks like nurturing, it looks like care, it looks like anger, it looks like pain. These things matter.

Rihab Essayh, As With All Warriors of Love, 2022, installation, McBride Contemporain | image: Guy L’Heureux

GPA

Even in the arts there is this expectation that we are not supposed to be emotional. What is even the point then?

RE

In my undergraduate degree, I was always making sure I made “clean work.” All white on white. I only recently started working with colour because I was terrified before of being told my work was feminine. Now I see this as my own internalized misogyny. While radical softness is often talked about from a feminist point of view, it also needs to be pushed further from an intersectional point of view. As women we’re already expected to be emotional, and then add that layer of “I’m not white,” and now I’m irrational on top of it. That denies all the labour I carry and my years of research. I might be told, “Your work is just intuitive.” And I say no, I’ve gathered this knowledge, and intuition is not devoid of reason. The personal in a place of criticism, of art critique, is still viewed as less worthy than a research practice. I have found this profoundly disgusting. For a field to be open-minded and leftist and people-oriented, this is the least open you can be.

GPA

The work you are doing to articulate the value of softness and care is important for all of us.

RE

Someone once said to me, “I don’t like to be mothered.” It got me thinking about the use of that word. Do they mean they don’t like to be overly cared for in a way that is limiting to their creativity, fine, but why use the word “mother”? These pejorative words are often still feminine. I don’t think it will change in my lifetime with the way woke movements cycle in and eventually disappear and no one is being held accountable long-term.

I think it’s important to not deny that we are living in a white patriarchal system. It is what bell hooks says: imperialist, white-supremacist, capitalist, patriarchy. These are so many words, but it is about understanding that they are all interrelated. I will work within the system because those are the parameters I have to navigate, but I will share my views when given the opportunity. I will never feel guilty about taking up that space, and I will offer opportunities to others. For this project, I really wanted to work with women, meaning anyone on the spectrum of femininity. I had a pyramid of who I wanted to work with, at the top was SWANA women. In the end, I worked with an Iranian woman, a Lebanese woman, an Algerian woman, an Egyptian-Armenian woman, and a Palestinian-Canadian woman. As someone creating in this world with the ability to hire people, I want to hire people who won’t necessarily get these opportunities otherwise. This is out of rectification and a sense of duty.

GPA

I wanted to talk about your use of materials. In your hands, fabric has a language of its own. You recently held a “slow stitching” workshop in Kingston. Can you speak about this idea of slow stitching and about your relationship to fabric in general?

Rihab Essayh, process image, 2022

Rihab Essayh, fabric samples, 2022

RE

I knew how to sew a line. A semi-straight line, let’s be honest. And then I just began learning through YouTube how to sew properly. Before that I was working with paper, folding paper, and I needed to heal from tendonitis. I was also craving and needing tactility. I am always interested in materiality. I have my fabric samples next to me right now. I work mainly with natural fibres, because working with fabric creates a lot of waste. The only non-natural fibres are my threads because I got these on Marketplace. I am learning a lot from craft and fashion YouTubers.

Working with fibres and dyes has given me this great experience of tactility. It also forced me to put a lot of attention on what I am wearing. And I’ve developed this awareness that I am also being held by fabric constantly.

The slow stitch workshop was a mending workshop. I was using this idea of the fabric holding us, and fabric as armour. The workshop was about learning to take care of these fibres that hold and protect us. It was about learning how to fix common tears in the fast fashion products we buy and how to mend seams that have been cheaply made. I learned hand stitching by watching historical fashion YouTubers. Garments made in the 1600s still exist because they are strong.

Rihab Essayh, process image, 2022

In my video, the performer’s pants are two types of muslin, the top is silk habotai, which makes everything look slow motion, the visor and veil are silk organza. I love silk so much, because it is a protein-based fibre. It is a lot like hair. If you bleach it, it melts away. It has a really lovely strength. If I could work only with silk, I would, I just can’t afford it. The armour was made out of stiffened silk organza. Gosh I hate polyester. I love the flexibility of natural fibres. They contain knowledge that polyester just doesn’t have.

GPA

Do you think your work engages with nostalgia? Is it nostalgic?

RE

Nostalgia is dangerous. I remember for the longest time I was using this Welsh word hiraeth in my artist’s statement. It means a particular kind of homesickness or nostalgia, and this sentiment is something that stays with me. But it is a little different from nostalgia alone. Nostalgia holds a deception because we can never go back and re-experience something. The situation is different and we are different. The good old days don’t exist. There is no such thing as going back. This is the farce of all conservative governments – in Italy, Quebec, the US – promising a return to how things were before. This politicized nostalgia is deceiving, but longing is real.

GPA

Your work reminds me of something Tanya Tagaq writes in her novel Split Tooth. She says, “Time is not rushing by. Time does not obey the clock. Time obeys physical laws like matter does, but it can control matter as well. Time is matter. Time is alive.” How does time work in your art?

RE

I love that. That is a good question. I feel like time is linked to emotion. If I’m enjoying myself time goes so fast, and I feel like I lose full days. And if I’m suffering time is slow and lingering, and I go through pain. Something that I am trying to do in these spaces is to make joy go slow. Can we make joy linger?

Rihab Essayh, As With All Warriors of Love, 2022, installation, McBride Contemporain | image: Guy L’Heureux

Rihab Essayh was born in Morocco and raised in Tiohtià:ke/Montréal. Essayh is an interdisciplinary artist whose large-scale, immersive installations create spaces of slowing down and softening. Her research considers issues of isolation and disconnection in the digital age, imagining futurities of soft-strength and social reconnection by proposing a heightened attunement to colour, costume, tactility and sound. She completed her MFA at the University of Guelph in 2022. Her work has been shown at the Art Council of Montreal, Centrale Powerhouse Gallery, FOFA Gallery, Never Apart, the plumb, and the Art Gallery of Guelph. Her work is also currently on view as part of solo exhibitions in Arsenal Toronto's project space and Union Gallery.

Georgia Phillips-Amos is a writer, editor, and researcher whose writing on contemporary arts and literature has been published in Artforum, Border Crossings, Frieze, The Village Voice, and more. She is currently a PhD candidate in Art History at Concordia University. She lives in Guelph, Ontario, with her partner and their two young children.